Pádraic Ó Conaire's Deoraíocht/ Exile

Tá úrscéal mór Phádraic Uí Chonaire ar fáil anois san Fharóis.

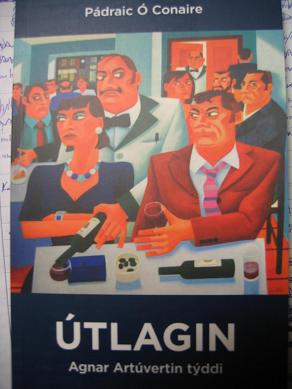

This publication is shown because Pádraic Ó Conaire's masterpiece Deoraíocht/ Exile is now available in Faroese, a rare language spoken on islands not considered to be a part of the territory covered by the European treaty, but under the jurisdiction of Denmark. It is connected to the story of monks and to Ireland in more than one way.

According to Gabriel Rosenstock, Deoraíocht (Exile) is a neglected masterpiece by Pádraic Ó Conaire, who he considers to be one of the most European-minded of early twentieth-century Irish-language authors. Gabriel Rosenstock continues the story by explaining how he assisted in the rebirth of this novel in Faroese by matching Ó Conaire with another gifted eccentric, Agnar Artúvertin. Thanks to his translation, the novel is now available in the Faroese language. To give a first contact with that language, he suggested the following passage which he explains in the context of the overall novel as being a touching moment for him.

ÚTLAGIN

– skaldsøga –

eftir Pádraic Ó Conaire

Agnar Artúvertin týddi

Forlagið Gwendalyn 2012

Extract from that translation into Faroese (page 151 - 152)

Eg fór glorvandi gjøgnum kavan, glaður fyri at tað

var eydnast mær at eyðmýkja tey, misbjóða teimum,

æruskemma tey.

Men hvar var eg nú? Í onkrari tvitnari bakgøtu.

Kavin eltur til runu undir fólkatraðki. Alt grátt á liti.

Menn, kvinnur og børn stóðu í trunka. Øll á gosi. Óttafull.

Ørkymlað.

Har liggur ein ung kvinna mitt í teirri gráu og skitnu

evjuni. Hon liggur púra still. Ein maður stendur uppi

yvir henni, og ein stór sleggja stendur við síðuna av

honum. Hann hevur stíva kenning; fimm mans halda

honum – nakrir teirra vilja sleppa at sláa hann kaldan

beinanvegin. Hatta er kona hansara, sum liggur í kavanum.

Sleggjuna á vegnum eigur hann (varð hann ikki

sæddur við henni í morgun?), og kanska kvinnan ikki er

deyð, men tað er nýføðingurin í øllum førum . . .

Har kom ein lækni og ein politistur. Níðingurin varð

handtikin. Hálvdeyða kvinnan varð borin avstað. Eitt

lak varð sveipt um nýføðingin, og farið varð í líkhúsið.

Nú fór aftur at kava, men fólk vóru standandi og

fóru ikki avstað. Tey tykjast standa sum negld, og her

koma fleiri fólk aftrat. Tað tykist renna av teimum,

sum høvdu drukkið. Løgreglan má halda teimum burturi

frá tí bletti, har ið kvinnan var fallin í kavanum.

Tey tosa um ta andstyggiligu gerð, sum her var gjørd.

Og beint áðrenn teir fóru avstað við manninum og

kvinnuni og tí nýfødda barninum, ið føddist í kavanum,

hugsaði eg við mær sjálvum, at hasi smáu, tendraðu vindeyguni

í øllum hesum myrku, lítlu húsunum báðumegin

við mintu um eyguni á onkrum óndum ódjóri, sum ikki

mundi dáma mannaættina nakað serligt. Tí hugdu hasi

eyguni ikki háðandi at hesum lítla trunkanum av fólki í

vátum spjørrum, at kvinnuni, ið lá hálvdeyð í kavanum,

at nýføðinginum, sum aldrin slapp at síggja sólina, og at tí

drukna pápanum, sum løgreglan fór avstað við? . . .

Eg gjørdist sligin av ræðslu.

Tað setti at hjartanum av teirri andstyggiligu, teirri

andskræmiligu gerð, ið varð gjørd her á hesum staði. Eg

orkaði ikki at vera her longur. Tað ógvusliga við gerðini,

ið her varð gjørd, dró fleiri túsund at staðnum, men meg

rak hon burtur. Eg vildi bara sleppa so langt burtur sum

gjørligt. Slíta alt samband við tað ótespiliga lív, eg so

leingi hevði livað. At skunda mær at rýma undan teirri

feitu konuni. Hevði eg gift meg við henni, hevði tað

bara endað við, at eg hevði dripið hana, eins og hasin

fulli lúshundurin hevði dripið konu sína.

Eg kom til sjúkrahúsið, og har stóð ein smádrongur í

kavanum uttan fyri dyrnar. Hann stóð og græt so sáran.

Eg kendi hann. Hevði eg ikki ofta sagt søgur fyri honum

og fyri øllum hinum smádreingjunum? . . . Hatta var

sonur tann mannin, sum plagdi at geva konu síni tveir

mussar hvønn morgun, sonur tann mann, sum nú hevði

givið konu síni sleggjuna í skallan.

Pilturin fór inn á sjúkrahúsið aftan á líkinum av

mammu síni. . . .

Eg fór hólkandi avstað, og fanansskapurin skrykti í

mínar hjartarøtur.

About the translator Agnar Artuvertin, Gabriel Rosenstock explains a bit more how this connection came about.

"I have translated poems and stories by Artúvertin into Irish. The book is called Ifreann (Hell), with a hellish cover by Pakistani artist Mohsin Shafi. Before the publication of Ifreann, Artúvertin was relatively unknown in Ireland. Now he is completely unknown.

http://www.litriocht.com/shop/product_info.php?products_id=6705

I am very happy to see Deoraíocht in Faroese. The author had lost his head in more ways than one: in 1999 four men from County Armagh, Mr Garret Leahy, Mr Gavin McNaney, Mr John McManus and Mr Garry O' Connor decapitated him - (i.e.his statue in Eyre Square, Galway). My own novel, incidentally, is called My Head is Misssing but has nothing to do with the Galway incident (as far as I know). It has a cover by the Indian artist Amit Kalla:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/My-Head-Missing-Gabriel-Rosenstock/dp/1908817801

I tried to bring Agnar to Ireland for the launch of Ifreann but, as far as I remember, the Danes would only offer him €100.00 or so and this would not go very far in the Dublin pubs where our launch was going to happen (i.e. in a dozen or so pubs more or less simultaneously).

You may contact Agnar at: agnarster(at)gmail.com

Our pool of consciousness widens. Actually it doesn't. It's as wide as Original Mind. It is simply becoming conscious of itself!

Very few people go to bed at night thinking of Faroese (not even the Faroese). We must change all that!

Let's hear from Agnar on your site and how he enjoyed translating Deoraíocht into Faroese and whatever other little miracles he cares to mention...

Best,

G.

Agnar Artúvertin

"The novel begins with acquainting the reader with a young Irish man who has lost his arm and his leg due to being run over by a car while looking for work. The rest of the novel is about his slow downfall in various hostels in London. He becomes more and more poor and hungry, and takes bad jobs where he is exploited and made fun of. It's a very tragic story, and in the end he starts to hallucinate from hunger, and after his uncle and cousin come to London to bring him home to Ireland, he escapes them and goes wandering in the streets

The extract I sent you begins here. In a back alley, he sees a dead woman lying in the snow, and her drunken husband is standing beside her with a sledge-hammer. He has killed her. The husband is taken by the police, and the protagonist is existentially nauseated by what he has seen, and goes away, and when he walks past the hospital, he sees a little boy crying - it's the son of the woman who has been killed. The protagonist walks unsteadily and shocked away, "and ten thousand devils are gnawing at his heart".

I think this passage is very touching - that's why I chose it.

I think Gabriel can procure the extract in English?"

- Agnar

Gabriel Rosenstock gave the link to the Enlish-language version:

http://books.google.ie/books?id=gl7JuPH7zp8C&pg=PA9&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=4#v=onepage&q&f=false

A further explanation by Agnar about the importance of this translation work

"I think Útlagin (Exile) ranges among the absolute top novels that I’ve read, and is definitely the best one that I’ve translated, by far. And I’ve translated seven novels. It went straight to my heart when I first read it, and I’m very happy that Gabriel Rosenstock made me aware of this Irish author.

I’ve tried to introduce this translation in the Faroe Islands by drawing attention to the fact that we and the Irish are similar - both abused by bigger nations for many centuries (the Irish by the English, and the Faroese by the Danish) - and that we can still only read one other short Irish work - by Joyce - in Faroese.

The Faroese mind has always been linguistically schizophrenic. When the Danes tried to make Faroese extinct, the Faroe Islanders divided, in their minds and every-day life, the two languages, ie. they spoke Faroese normally, but wrote and spoke to the authorities in a Danish, tinted by Faroese and full of loosely translated Faroese words. Danish never managed to make Faroese extinct, like the languages of other imperialists have done to many other small language areas. I think this is a fact that we have in common with the Irish. It’s very fascinating.

But today, Irish-Gaelic is threatened by extinction. Faroese is not. One reason for this, I think, is the geographical location of Ireland and the Faroe Islands. The latter is far away, isolated, small and has bad weather, and is not attractive to move to. While Ireland is more attractive and more known, and is therefore overrun by immigrants. Foreigners who move to the Faroe Islands, are mostly eccentrics and geniuses who become absorbed into the Faroese society and culture. Many of them even become Faroese nationalists. Many Irish writers moved from Ireland, while Faroese writers always stayed on the islands of their birth.

Most Faroese translations are made from English, Norwegian and Danish, and this is how it has been since the first books were published in Faroese about a century ago. That’s a shame, because all people here can read those languages, but luckily, we’re starting to translate literature written in languages that people here can’t read, like German, Estonian, Russian, and Irish-Gaelic

The Faroese need to become aware of master-pieces from other more unknown nations, and translate and publish them. I’ve done my share, but I keep working and doing more."

« CATHAL Ó SEARCAIGH | Offshore on land by Liam Ó Muirthile »