Public Truth and Public Space by Bart Verschaffel

The meaning of concepts and conceptual fields is not laid down solely by definitions and descriptions. A definition is often inadequate to make it really clear what a term means or signifies. The meaning of terms or clusters of terms is then ‘illustrated’ by referring to ‘cases’ which are considered exemplary or prototypical, by referring to a field of experience or reality as the ‘scope of application’ of a term or term cluster, and/or by familiarity with ‘good practice’ in using the terms. Knowing how words ‘work’ and knowing how to use them goes hand in hand with the sense that words have a grip on things and assures the user that the terms he uses are ‘valid’. Certain scientific disciplines engage in very clear, abstract thinking. Geometry, for instance, can define a square in very clear and unequivocal terms. But many other knowledge disciplines are unable to incorporate their concepts and conceptual structures in a unifying theory. In these cases, grasping the meaning of a term is inextricable from the sensorial and practical familiarity with ‘cases’ or with a field of reference. When concepts are forged from words that are connected with that field of reference by a prereflexive use, familiarity with that field of reference becomes a precondition for grasping the concepts themselves: every concept is a metaphor; the prior knowledge of a field of experience informs the theoretical reflection. For example, take the arsenal of concepts we use to describe knowledge or knowing: the vocabulary is dominated by visual metaphors. Very many words refer either to light and dark, or to perspective. It should be possible to write a history of epistemology by tracing the shifts in this terminology. This raises the question of what ‘knowledge’ or ‘insight’ could mean to a person who lacks the experience of ‘seeing’, that is to say: who has never seen light fall on something enveloped in darkness, or who does not know the difference between a frontal view and a lateral view. If this is true of the conceptual apparatus of epistemology, it certainly applies to many other disciplines. What about the conceptual apparatus of politics, for instance, or of the judicial system? What does ‘freedom’ actually mean? What does ‘public space’ mean’? Is the ‘private’ a space?

The prototypical reference, that grounds the meaning of freedom in pre-philosophical terms, i.e., simply says what ‘freedom’ amounts to, is, in my view, a double one: being free to speak one’s mind and being free to go where one pleases. Freedom – in every possible meaning of the word, in any possible scope of application – is always somewhat like being able to speak one’s mind or to go where one pleases. ‘Unfreedom’, then, is anything that amounts to/’feels like’ being unable to say what one thinks or go where one wants. At a basic level, therefore, freedom and the lack of it are connected with experiences familiar to everyone or at least easy to imagine, such as what it means to be locked up, obliged to say something, or to be barred from an entrance or stopped at a border. In other words, the experience of speaking ‘freely’ and moving ‘freely’ teaches us what freedom is. This experience continues to inform, as a metaphorical substratum, our conceptual and theoretical definitions of freedom, and is even their de facto standard measure. Definitions or meanings of ‘freedom’ that do not implicitly ‘check’ with these basic references sound implausible, seem counter-intuitive, and instantly lose their ‘validity’. (Conversely, any political discourse that manages to appeal directly to these basic experiences, or is able to use them to show that the actions or programmes of their adversaries curb the ‘freedom’ of speech or movement, will always win.)

In positive terms, freedom is the freedom to say what one wants to say and go where one wants to go, but – in the second, negative moment – freedom is also not being obliged to speak, i.e., being able to keep one’s opinion to oneself, and not being obliged to go anywhere, i.e., being able to stay ‘home’ when one chooses. A balance needs to be struck between these two sides of freedom. Moreover, in a free and democratic society, in which everyone is entitled to freedom and everyone is, in principle, entitled to an equal voice in the decisions that regulate society, there are a great many complex freedoms that all need to be geared to each other. It is here that the definition of freedom is spatialised with the aid of categories such as ‘the private’ and ‘the public’, or the private home versus the public/political space of the ‘agora/market’ and ‘the street’. The basic experiences which, in my view, constitute the metaphorical substratum of ‘political concepts’, are related to these spaces that literally delimit each other and effectively exclude each other. Each of these spaces has its own regime of ‘accessibility’ and its own limitations of ‘speech’ and ‘voice range’. The private and the public are ‘normally’, or in the first place, not seen as ‘dimensions’ or ‘aspects’ of life or of society, but as areas or spaces, as ‘places’ and relations between places in the world. Each of these spaces is governed by a specific ‘regime’. In the seclusion of the home, one can think and say what one wants, without anyone overhearing or even being entitled to listen in, and one can stay home when one does not wish to go out. In a democratic society, where everyone is entitled to this freedom (and therefore to ‘privacy’), this implies that these private spaces are closed off from the world in which everyone is free to move as they please, and therefore, that these spaces are effectively restrictions on that freedom. These private spaces are ‘inaccessible’. Freedom of movement is restricted by the ‘private’ spaces of others. But the rest of the world – the streets and squares – is still, in principle, ‘public space’. The public space is meant for free exploration, free association and free assembly. Freedom means that one can move about in this space and meet whoever one wants to meet. In a democratic society, where the decisions concerning society are, in principle, taken in public, this implies that the freely accessible public space is also the political space, that the political space is freely accessible to everyone, and that everyone has the right to listen, speak and be heard in the public space.

It is very important to realise that the ‘prototypical situations’ that ground and fill concepts are invariable cultural abstractions. Understanding freedom as ‘free speech’ and ‘free movement’ is connected with particular cultural and social premises. The notions of freedom of speech and freedom of opinion, for instance, presuppose, in principle, that the speech in question is addressed to a ‘public’ of equals, and that speaking and discussing is a kind of game with equal players that is settled purely by strength of argument or by power of persuasion. Whereas, of course, in real life, the players are never equal, because there are men and women, pupils and masters, old and young, clergy and laity, prominent citizens and the rank and file. Abstracting these positions in the game of the discussion implies a negation of certain aspects of reality, for the participants in the game are unequal to all intents and purposes. Many societies are not willing to play this game, because they believe that the presumed theoretical equality of speakers, which the modern West considers as one of the implications of the game logic of rationality, comes down, in reality, to a lack of respect, and to a discourteous and dangerous disregard for real positions and dignity. Similarly, ‘freedom of movement’ implies seeing the world as a ‘public space’, and public space as a homogeneously accessible space, open to free exploration and free initiative. For many cultures, this principle goes against the experience of what the world ‘really’ is. For many people and peoples, the world is not homogenously ‘available’, but heterogeneous, always already formed and already occupied by meanings. They deem it improper to roam through it freely, driven merely by one’s own desires or whims. In such a cultural context, therefore, the opposition private/public simply does not ‘work’ at all, or ‘public space’ means something quite different than in Western cultures. For instance, it may have a different meaning depending on whether it is applied to a man or to a woman. At the same time, however – and this too is an ‘anthropological fact’ – the aforementioned basic experiences, together with the spatial diagram they are based on, constitute the foundation of the legal and political reasoning that gave rise to the topic of this symposium.

In the last few decades, media theory, philosophical anthropology and architectural theory have all called attention, with increasing emphasis, to what may be called ‘the crisis of the place’. The importance of ‘place’ as an integrative and stabilising force in human experience is waning. The experience of time and space, work, communication and social relations is increasingly becoming mediated by a series of devices and systems that are diminishing the impact and meaning of ‘place’, and even the notion itself. The building of transport networks, and in particular, more recently, of communication and information networks, is radically redefining what it means to be ‘someplace’. At first – as ever – these devices and systems seem merely to lift old restrictions without affecting the form of the experience itself. The elevator seems to be merely a way of getting up the stairs faster, flying another mode of fast travel, the telephone merely a device for shouting over a very great distance, and the television a kind of ‘town square’. However, gradually, the realisation has dawned that these things are not what they seem. A person who has flown someplace has not travelled, and talking to someone on the telephone is something completely different from a face-to-face encounter. The most drastic change – the effect of communication networks – is probably that of completely disconnecting the act of speaking from a specific place: the place occupied by the speaker in ‘reality’ (that is, where his or her body is) has no bearing on the speaking and listening, and does not determine the distance over which the voice is carried. Virtual ‘contact’ and virtual ‘ubiquity’ demand that the body stays behind on the edge of the network. The speaker’s ‘real’ place and his or her body are no more than ‘residue’.

These developments immediately and radically affect the meaning and self-understanding of traditional architecture and urban planning. After all, architecture is the attempt to give people and things their ‘place’, to make places, and the experience of these places, as correct and strong as possible, and to bring structure and order to the human experience and human lives. One of the most elementary differences that architecture makes both clear and real is the difference between private and public, house and street or square, inside and outside. The architectural articulation of these differences involves an extremely subtle arrangement of space, with indications of borders and barriers, and of paths, crossings and thresholds. But architecture does not just create the material and very ‘objective’ circumstances within which society ‘works’. As it does so, it also immediately presents a picture of a possible world: it proposes a spatial expression of that society. However, this is on the presumption that, in every social process or every event, the place – that is, that which architecture and urban planning have shaped – is constitutive and that it also actually appears: the ‘place’ where one speaks or where the discourse or encounter take place is to society as a set or a backdrop to a game or to an event, and not as hardware to software. But how to – literally – place the ‘presence’ or ‘proximity’ of the telephone conversation? Designing a public phone booth is practically the hardest commission an architect can get. Architects are generally very pleased that mobile phones are doing away with the need for public booths, precisely because the event that takes place in such a booth will have nothing to do with its particular place. What is the place of a split image? I do not want to give many more examples here, but merely point out that the transformations in the concept of ‘place’ are not only making difficulties for architecture and urban planning, but are also affecting political and legal concepts. What does it mean when it is no longer possible to sharply define the distinction between ‘private’ and ‘public’, the relationship of the ‘public’ to the ‘political’, or the concepts of freedom and unfreedom in terms of space and accessibility? It is no longer self-evident to equate the private and the public with ‘home’ and ‘street’ or ‘square’, respectively, nor to identify street and square with the ‘political’ space. It is no longer self-evident to consider the private as a domain that is closed off from the world and borders on the public. The experiences that show, ‘intuitively’ and prototypically, what freedom and political participation amount to, are losing power and validity. They seem to be no longer ‘valid’, without having been replaced by others.

I will clarify this by presenting two analyses, which do certainly not cover the entire scope of the issue, nor even cover sufficient ground for drawing any conclusions. My sole aim at this point is to illustrate my point and present the problem.

In the first analysis, I will look at the status and the meaning of the house or residence, and closely related to that, at the presumption and expectation that the citizen has a fixed ‘place’ in society. The ‘fixed place’ should be taken literally here: today, a civil identity is connected to an abode or ‘domicile’. The domicile is the place where a person can be ‘reached’ and ‘addressed’. People are supposed to live somewhere. Living implies a durable connection with a place – a house or a flat – as well as an identification with it. Home is the place where one can talk to someone, where one goes to wait for someone and meet someone. It is the place that cohabiting people share with each other. The fixed place that grounds a life is considered as an essentially private space. The place where a person can be reached is also the place where that person withdraws from the public realm. But because the ‘exterior’ of the private space always borders on the public space – and because, in aristocratic and middle-class residential cultures, a part of the interior is explicitly conceived of as a public ‘reception space’ – the house (the façade and sometimes a part of the interior) does ‘uphold’ the public appearance. The house represents the person: it is perceived and read as a bearer of his or her social identity and – in the era of the individual – even as the expression of a personality. In other words, the house is a private space with a public face. The house is also on display; it is façade.

However, the massive introduction of transport networks and the fact that human relations and communications are now largely technically mediated through communication networks are reducing the impact and diminishing the import of this identification. They are reducing the representativeness of the home. First, because the transport networks increase people’s radius of action, making their social contacts more dispersed and one-sided. It is quite common these days not to know where or how one’s closest colleagues or associates live. The ‘public meaning’ or representativeness of the home is eroded even more by the new information and communication channels. Modern communication technology disconnects the home from the communication space where people meet ‘virtually’. In the virtual communication space, the house where real fingers ‘really’ type on the keyboard does not appear: the web page is the new ‘façade’. Inevitably, this erodes the representativeness of the home. When you can find a personal website via a single Google search and the Web often provides enough information to put together a file on a person, what meaning could a stone façade still have, or the furnishing of a living room?

This development is reinforced by the second generation of communication media. For the post and the ‘classic’ landline telephone, the domicile remains crucial: the telephone is plugged in at home. Messages – such as letters – arrive there and are picked up there. Letting messages pile up for a longer period of time is likely to get one in trouble. In first-generation communication networks (post, landline telephone), the contact is virtual or ‘delayed’, but the home continues to ‘mediate’ and ground a person’s life in a particular place. The home is ‘headquarters’ and therefore remains a meeting place. The ‘address’ is not yet a position in the network itself – like an e-mail address – and it is still a place in the world. The most recent means of communication, however (internet, mobile telephone) have divorced accessibility from ‘domicile’. Accessibility, speaking, and the meaning of what is said are no longer connected to the location of the speaker. Addresses are mobile, people carry their address on them, and they can be reached anywhere. They are their own headquarters. This has major implications for the way the space is used. Before the introduction of the mobile phone and wireless internet, appointments needed to be made well in advance, as a person who was already on his way could no longer be reached. These days, people use their mobile phones to agree ad hoc on where and when they will meet, based on the ‘positions’ of the persons involved at that moment. It makes no difference from which real place one plugs into the virtual space that guarantees the continual reachability of everyone and the ubiquity of all information. Even togetherness in private relationships is mediated by the new technology: when a mother and child both have a mobile phone, the mother is always ‘present’ and she knows at any moment where her child is without a house mediating this proximity. When ‘addresses’ thus become mobile and reachability is disconnected from domicile, the home loses its social importance and its representativeness. The private no longer borders on the new ‘virtual public space’ where everyone is virtually together, and (for the time being) one cannot see the ‘private spaces’ from the virtual ‘public square’. The houses therefore lose their ‘façade’ or face.

What do ‘privacy’ and freedom mean, what is ‘public space’, and how political is a public space, in the light of these developments? Architects and urban planners are not the only ones who realise that the traditional way in which the social structure and social relationships are translated into terms of space is no longer suitable. Even the basic images that supply the metaphorical basis of many political and legal principles or distinctions have lost their ‘validity’. How ‘isolated’ is a person who carries a mobile in his pocket? How public is a telephone conversation held by a passenger on a train? What does it mean to be free to move in a ‘public’ space that is not at all ‘anonymous’ anymore? (The average Londoner is filmed by security cameras 300 times a day.) How ‘political’ is a ‘public square’ when virtual spaces have opened up besides this ‘real’ space, which ‘virtually’ bring together millions of people? In any case, the concept of space in which public and private spaces delimit and exclude one another is no longer adequate, and the home has lost a lot of its social importance. The home seems to be increasingly acquiring or set to acquire a temporary, intimate and secondary quality, practically without a public exterior.

The second development that deserves attention because it is the accepted spatial expression of political and legal concepts – and therefore, in my view, affects the intuitive understanding of those concepts – is complementary to the loss of representativeness of the home. It is a double development, connected to the two possibilities offered by the public space: freedom of association and freedom of assembly. The two developments are, first, the loss of anonymity in public spaces, and secondly, the loss of political relevance and of representativeness of those urban spaces – of streets and squares.

First, the loss of anonymity. Freedom implies freedom of movement. However, just being free to move without anyone interfering, while continuously being followed or watched, is intuitively no longer perceived as ‘freedom’. And yet that is the effect of the new information networks. People who move freely leave traces wherever they go. The development of the new information and archiving techniques have turned the world into one large virtual carpet of snow in which every action leaves tracks that can be combined and used in ways that are uncontrollable and unpredictable. How ‘private’ is life indoors when housekeeping purchases, telephone calls, library use, electronically purchased train tickets and internet surfing behaviour are all saved and stored someplace (automatically and as a matter of course, even without anyone being curious)? It has become difficult to think of ‘privacy’ in ‘spatial’ terms, i.e., in terms of ‘private space’ and ‘seclusion’.

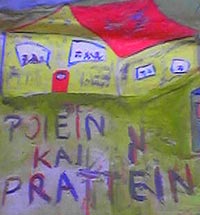

Next: the representativeness of the urban space. Before the new communication technologies were introduced, meeting someone or attending a political meeting involved going ‘outside’, leaving the private space and going out into the ‘public space’. The public space even mediates in private relations: to meet or visit someone, you have to venture out of doors. What’s more, in a democratic society, the public space, and in particular the city, made up of ‘streets and squares’, was – and still is – identified with the ‘political space’: essentially, it is a space for discussion, for protest and consensus, of argumentation and decision-making. The architecture and urban planning that give material shape to the public space has defended the public space and the city in this sense, especially since the seventies, against the functionalisation and objectification of that space as a result of the large-scale construction of the transport networks, and against the ‘voiding’ of that space by the creation of that second, virtual, technically mediated communication space. The starting point of this tendency in architecture was phrased in succinct and simple terms by Louis Kahn in a lecture he gave to architecture students in 1972, in which he summarised an argument that he has already presented at the last CIAM Congress in Otterlo in 1958: ‘The city is only a part of the inspiration to meet.’ [1] From this, it follows how architects and urban planners should think about architecture and the city: ‘but if you think of the street as a meeting place, if you think of the street as being really a community inn that just doesn’t have a roof... And the walls of this meeting place called the community room, the street, are just the fronts of the houses...’ [2] ‘And if you think of a meeting hall, it is just a street with a roof on it.’ [3] It is abundantly clear that Kahn was defending something that was disappearing.

My point is certainly not to downplay the social importance of the street. On the contrary, social life still consists to a great extent of pre-modern relations that are based on literal, physical proximity: being neighbours, sharing the same physical space. And these very real and physical relations are very important, in particular for those age and social groups that are less mobile than others. But it would be totally wrong to still consider the street as the primary political space, as the ‘agora’ and therefore as the ‘speaking place’, just because it (still) remains an important social and existential space. What needs to be reformulated is the relationship between ‘speaking’ or ‘having a voice’, between ‘speaking in public’ and space. It is this connection between the public space, the ‘agora function’ and discourse that has become much less clear-cut.

The key argument here is that the public space – the space of streets and squares – is not a speaking place anymore, but has become a place of spectacle and spectatorship, and has therefore lots its political relevance. The public space is now the space where one is free to move, to look and to choose: it is the space of consumption. The dominant social logic that now regulates people’s relationships with what lies outside the private realm and that determines the social rules in the ‘public realm’ is not the logic of society and consultation, but the logic of consumption. The underlying primitive ‘experience of freedom’ does not seem to be that of being free to go wherever one wants, but rather that of being free to buy whatever one wants. However, this freedom has a very deceptive political relevance.

The logic of consumption is fundamentally different from the logic of need and necessity. The traditional (urban) market is a public space where interests meet one another and where the parties have to arrive at an agreement – a ‘price’ – through negotiation. This makes the market into an important social space, where business relations are made and maintained and where shared interests and agreements are woven into a conflictive but very real social tissue. However, consumption does not happen on the marketplace, but in solitude in front of the show window. Consumption does not start from needs and is not geared to negotiation and agreement. Its driving force is desire. It demands a daydream atmosphere in which a person is left alone in the company of a quantity of things, forgetting about money and reality for as long as possible, or until he or she unexpectedly and accidentally comes across the object that is ‘missing’, which then transforms, in a surprising-mysterious way, into an ‘object of desire’. In the second movement, the shopping street or the city itself is turned into one large shop window, in which the consumers, who have fitted themselves out with an ‘image’ through their buying behaviour, are exposed to the critical gaze of all the others, and start judging those others themselves, as it they were objects in a shop window. However, these forms of ‘encounter’, the purchase of a thing, or the attention paid to a person’s looks, or the refusal to look at any thing or to buy anything, are never the result of negotiation or discourse. They cannot be measured against a need or a necessity. Consequently, the consumer can never be asked to give reasons. What decides is the irrational ‘I want’ or ‘I don’t want’ (to which ‘I want to be able to want’ = ‘I want money’ is the underlying desire). Consumer logic is utterly based on personal desire and personal taste and sees no problem with that. It offers the experience of a freedom that is not answerable to anything or anyone. But this roaming and freely desiring subject is not a political subject. A consumer’s choice, precisely because it is divorced from any conviction or argumentation, has no political import and therefore cannot be considered as the expression of an opinion. For the consumer does not distinguish the way one elects politicians from the way one chooses a car. The dominant myth of the street is de facto the ideology of populism.

In the light of the objectification of the public space by technology on the one hand and the individualisation of the public space as part of commercial logic on the other, I believe that the situation calls for a reconsideration of the place and meaning of the so-called semi-public spaces. For these spaces, which remain after the decline of the civil city, are spaces that are still mainly constructed as actual speaking places. At the same time, the semi-public spaces are essentially theatrical. This implies that they are spaces with a threshold. They are spaces that are only conditionally accessible – they can be entered on condition that one plays along. Because the theatre, like the school, the city hall, the library or the museum, is a separated public space. This separation automatically implies violence and exclusion: the separated space is dominated by power; certain groups have easy access while others are barred. But the threshold is more than an obstacle. It also marks a transition from the street to a conditioned space: one may enter the theatre or the museum on condition that one ‘plays the game’ and takes part in hat goes on inside it. The university, the city hall, the library, the museum – as well as a session of parliament, or a court – are theatres. The theatre is an exceptional situation in which not only the actors but the spectators too are cast in a role, and must leave behind at least a part of themselves on entering the playing field. Just like the actor is not himself when he plays a role, the people who play the audience in the theatre are no longer ‘themselves’. They are participants in a discussion that goes on within the space of an institution. The street certainly offers a spectacle, which can be fascinating from time to time, but it is no theatre: here, consumers do not play a role, but are simply ‘themselves’.

Modern civil societies have divided social life into different spheres which each have their official logic and specific activities. The decisions that are taken in each sphere are checked against the specificity of the sphere. For instance, religion and the acquisition of knowledge are different from business and from national defence, law from morality, art from science and from sports, and the private sphere of life differs from public life. The autonomy of these spheres is relative and must always be negotiated with adjoining or overlapping spheres. Although this autonomy is therefore a fiction to a certain extent, it does open up, for each sphere, a playing field that is governed by a specific logic. This logic determines the grounds to which one can refer and excludes other arguments, which are valid in other spheres or fields. The game logic is always imposed and works as if, because in each field, there are de facto always different forces and motivations at work. The invoked reasons and goals are always cover-ups and pretexts: all the social and psychological mechanisms and all the motives and impulses that determine human behaviour everywhere are fully in force in every field. However, the point is, that, within a game, one cannot invoke the reasons that are actually at play. One must be capable of at least hiding them and, on top of that, one must come up with plausible arguments that are valid in that particular game. One must at least plausibly pretend that law is really about doing justice; that science is dedicated to the disinterested search for the truth and for insight; or that art is not about money, but is practised for its own sake. Whoever wants to play is obliged to play a part, to leave his or her ‘self’ behind in the dressing room and to play or stage the actor that is postulated by the game itself. And all those who play the game also substantiate the whole enterprise. Their ‘pretending’ is what turns the game into a real event: the decisions taken within a specific field must be ‘plausible’ and are thereby effectively tested against principles that are valid within that field. Rationality needs theatre to live.

When we consider the rules of play of most social fields or decision-making domains as a form of rationality, we can state that the world is certainly not actually or really ‘rational’, but that some social domains are regulated in an exceptional way on account of the players participating in the fiction that the domain in question is ruled by a form of rationality – they insist that actions are checked against principles. In the civil culture of the West, the existence of these autonomous fields is ensured by institutionalising them. An institution is always also a circumscribed space. It is important that their autonomy is partly assured and represented by means of architecture. The different institutions each have their own recognisable place: courtrooms, churches, libraries, museums, theatres, auditoriums. This architectural independence implies that, each time a playing field is demarcated, a provisional public space is created and defined. The building represents the specificity of the field and effectively circumscribes a playing field that is rules by the logic of that field. The spaces are public spaces: anyone can enter them, but only on condition that they are willing to speak ‘the language of the institution’, i.e. at least to pretend that the game is true. The architecture therefore creates a threshold. It indicates the boundaries of an area of relative autonomy, and enforces a contract: anyone who enters a theatre or a museum accepts that they are ‘participants’ and therefore accept ‘the business’ of the theatre or of art as their own to a certain extent.

It is a debatable question whether – or perhaps: how – traditional spaces, or the civil city-of-streets-and-squares, has ever been a ‘conditional public space’. But it is certain that, in specific circumstances, the so-called ‘public space’ has really been a political space, i.e., a space where the individual took up a role and ‘took part’ in a joint event or a ‘general interest’, by participating in the discussion on decisions, or by affirming the shared values and principles in his or her behaviour. Little seems to have remained of that in the way the public space is shaped and experienced in the contemporary city and landscape. Rather, the street has become a myth: a powerful reference in a mediatised populist discourse, that imitates and evokes the ‘street’ and ‘freedom of speech’ in the media space. The reality of the ‘public consumption space’ and of the unorganised media space is an endless juxtaposition in which everything is uttered without ever eliciting a critical reaction and without checking against tradition. In these circumstances, the political importance of the institutional spaces, which still literally divide the private from the public and check the public space against criticism and tradition – against what has been said before – seems to be crucial.

The existence of ‘conditional public spaces’ or of institutional spaces is a precondition for criticism. Every institution imposes and restricts and excludes, but at the same time, because certain social and psychological mechanisms lose their force in it, it is also a refuge or sanctuary and makes room for criticism. Because, towards the outside,others can be reminded of the autonomy of the field: against religious powers, one can state that religious considerations have no weight in court; against the social consensus, that pedagogic reasons do not count in the theatre; against politicians and managers, that the acquisition and management of insight or knowledge is different from making a profit. A museum is no discotheque, a school is no church or mosque, a company is not a family. Within the institution, the principles that determine the game can then, ideally, be played off against the way the institution actually plays the game: a minority or an individual can create some leeway or liberty by evoking those principles, against the intrinsic sluggishness and mediocrity of every institutional operation. That is why it is essential, also for art and culture, to confirm and reinforce the institutions while also constantly attacking and breaking them open from the inside. Criticism aimed at the institute in itself, on the contrary, undermines the possibility of criticism; and the trend to counter the slowness and bureaucracy of every institution by dynamising and dismantling it, introducing a new logic – e.g. rethinking the concept of the museum or the university as an ‘enterprise’ and giving it a business-based structure – is extremely dangerous and perverse. The autonomy of the field is eroded and the margin for freedom and criticism shrinks quickly.

The indifferent or dismissive attitude of architecture towards the specificity of the institutional spaces shows a lack of awareness of the nature and importance of these so-called ‘semi-public’ spaces. Semi-public spaces are mistakenly believed to be less public spaces. For similar reasons, the ‘wholly’ public street is falsely held to be the most important public space, and the place where it is most important for society to be successful. But this view loses sight of the fact that, within those institutions, large parts of the social activity can be ‘conditional’, and that these ‘conditions’ guarantee that certain improper forces and interests can be put ‘out of action’. This implies, for instance – depending on the circumstances and the region where a person lives – that the logic of the ayatollahs or that of the managers can be kept outside the university, precisely because a university is a university and not a mosque or a company. A field that loses its autonomy is colonised – by a political system that cannot tolerate civil liberties or by the consumer logic of the street. In this process, one also loses sight of the fact that the ‘conditional’ nature of an institutional field also applies to the visitor. The visitor is assigned a role, a responsibility, and a dignity. The awareness of this role implies that encounters within the institutional space are not spontaneous, informal, or ‘ordinary’, but are mediated by the ‘object’ that is embodied by the institution. It means strutting is allowed on the streets but not in the museum, and that the superb freedom and irresponsibility with which a customer chooses a new car, a travel destination or a television programme do not come into play when that same person enters a museum or wants to study, precisely because a museum has to show what the museum believes is important, and because a school must introduce its students to knowledge, and acquiring knowledge is not like buying commodities. In the civil society, a large part of the social decisions are still taken within these autonomous, institutionalised fields. The processes of dismantling these institutions and installing the logic of the street largely restrict the possibilities for working freely in these spaces, and reduces the room for criticism. For an individual, a minority or an opposition cannot survive in an unorganised mass. They can only provide a counterforce against slowness, mediocrity, fear and corruption within the institution, by taking advantage of the leeway it offers and by making clever use of the principles of the institution.

To sum up, I believe it is important to clearly formulate and realise that crucial and formative conceptual structures, such as the distinction between the private and the public, and highly important presumptions, such as the idea that a public space is almost by definition also a political space and vice versa, are gradually becoming ‘false’ because the relationship between speaking and space is fundamentally changing. Secondly, that it remains very important, in this respect, to affirm and use those spaces that still fit into the traditional ‘spatialisation’ and to work with those contrasts – institutions and places of ‘public discourse’, such as this auditorium, or a museum. For the time being, they are necessary to talk and think about what is happening ‘outside’, in the streets and in the new, virtual communication space.

The prototypical reference that grounds the meaning of ‘freedom’ in pre-philosophical terms, i.e., that simply says what ‘freedom’ comes down to is, in my view, a double one: being free to speak one’s mind, and being free to go where one pleases. Freedom – in every possible meaning of the word, in any possible scope of application – is always somewhat like being able to speak one’s mind or to go where one pleases. ‘Unfreedom’, then, is anything that amounts to/’feels like’ being unable to say what one thinks or go where one wants. At a basic level, therefore, freedom and the lack of it are connected with experiences familiar to everyone or at least easy to imagine, such as what it means to be locked up, obliged to say something, or to be barred from an entrance or stopped at a border. In other words, the experience of speaking ‘freely’ and moving ‘freely’ make clear what freedom is. This experience continues to inform, as a metaphorical substratum, our conceptual and theoretical definitions of freedom, and is even their de facto standard measure. Definitions or meanings of ‘freedom’ that do not implicitly ‘check’ with these basic references sound implausible, seem counter-intuitive, and instantly lose their ‘validity’.

In positive terms, freedom is the freedom to say what one wants to say and go where one wants to go, but – in the second, negative moment – freedom is also: not being obliged to speak, i.e., being able to keep one’s opinion to oneself, and not being obliged to go anywhere, i.e., being able to stay ‘home’ when one chooses. A balance needs to be struck between these two sides of freedom. Moreover, in a free and democratic society, in which everyone is entitled to freedom and everyone is, in principle, entitled to an equal voice in the decisions that regulate society, there are a great many complex freedoms that all need to be geared to each other. It is here that the definition of freedom is spatialise, with the aid of categories such as ‘the private’ and ‘the public’, or the private home versus the public/political space of the ‘agora/market’ and ‘the street’. The basic experiences which, in my view, constitute the metaphorical substratum of ‘political concepts’, are related to these spaces that literally delimit each other and effectively exclude each other.

Each of these spaces has its own regime of ‘accessibility’ and its own limitations of ‘speech’ and ‘voice range’. The private and the public are ‘normally’, or in the first place, not seen as ‘dimensions’ or ‘aspects’ of life or of society, but as areas or spaces, as ‘places’ and relations between places in the world. Each of these spaces is governed by a specific ‘regime’. In the seclusion of the home, one can think and say what one wants, without anyone overhearing or even being entitled to listen in, and one can stay home when one does not wish to go out. In a democratic society, where everyone is entitled to this freedom (and therefore to ‘privacy’), this implies that these private spaces are closed off from the world in which everyone is free to move as they please, and therefore, that these spaces are effectively restrictions on that freedom. The freedom of movement is restricted by the ‘private’ spaces of others. But the rest of the world – the streets and squares – is still, in principle, accessibile ‘public space’. The public space is meant for free exploration, free association and free assembly. Freedom means that one can move about in this space and meet whoever one wants to meet. Moreover, in a democratic society, where the decisions concerning society are, in principle, taken in public, this implies that the freely accessible public space is also the political space, that the political space is freely accessible to everyone, thus that everyone has the right to listen, speak and be heard in the public space.

It is important to realise that these ‘prototypical situations’ that ground and fill concepts are cultural abstractions. Understanding freedom as ‘free speech’ and ‘free movement’ is certainly connected with particular cultural and social premises. Many societies for exemple are not willing to play the game of free speech, because they believe that the presumed equality of speakers, which the modern West considers as one of the rules of the game logic of rationality, comes down, in reality, to a lack of respect, and to a discourteous and dangerous disregard for real positions and dignity. Similarly, ‘freedom of movement’ implies seeing the world as a ‘public space’, and public space as a homogeneously accessible space, open to free exploration and free initiative. For many cultures, this principle goes against the experience of what the world ‘really’ is. But I will not go into that now. I start from the ‘anthropological fact’ that the aforementioned basic experiences, together with the spatial diagram they are based on, constitute the foundation of the legal and political reasoning that gave rise to the topic of this symposium.

In the last few decades, media theory, philosophical anthropology and architectural theory have all called attention, with increasing emphasis, to what may be called ‘the crisis of the place’. The importance of ‘place’ as an integrative and stabilising force in human experience is waning. The experience of time and space, work, communication and social relations is increasingly becoming mediated by a series of devices and systems that are diminishing the impact and meaning of ‘place’, and even the notion itself. The building of transport networks, and in particular, more recently, of communication and information networks, is radically redefining what it means to be ‘someplace’. At first – as ever – these devices and systems probably seem merely to lift old restrictions without affecting the form of the experience itself. The elevator seems to be merely a way of getting up the stairs faster, flying another mode of fast travel, the telephone merely a device for shouting over a very great distance, and the television a kind of ‘town square’. However, gradually, the realisation has dawned that these things are not what they seem. A person who has flown someplace has not travelled, and talking to someone on the telephone is something completely different from a face-to-face encounter. The most drastic effect of communication networks is probably that of completely disconnecting the act of speaking from a specific place: the place occupied by the speaker in ‘reality’ (that is, where his or her body is) has no bearing on the speaking and listening, and does not determine the distance over which the voice is carried. Virtual ‘contact’ and virtual ‘ubiquity’ demand that the body stays behind on the edge of the network. The speaker’s ‘real’ place and his or her body are no more than ‘residue’.

These developments did immediately and radically affect the meaning and self-understanding of traditional architecture and urban planning. After all, architecture was considered as the attempt to give people and things their ‘place’, to make places, and to make the experience of these places, as rich and strong as possible, thereby bringing structure and order to the human experience and human lives. One of the most elementary differences used to make a world legible and meaningful, a difference that traditional architecture makes both clear and real, is the difference between private and public, between house and street or square, between inside and outside. The architectural articulation of these differences involves an extremely subtle arrangement of space, with indications of borders and barriers, and of paths, crossings and thresholds. But architecture does not just create the material and very ‘objective’ circumstances within which society ‘works’. As it does so, it also immediately presents a picture of a possible world: it proposes a spatial expression of that society, it represents values. A doorstep is not only an obstacle, it also is a sign. However, this only counts on the presumption that, in every social process or every event, the place – that is, that which architecture and urban planning have shaped – is constitutive and that it also actually appears. Places can only carry meaning when the ‘place’ where one speaks or where encounter take place, is to society as a set or a backdrop to a game or to an event, and not as hardware to software. But how to – literally – locate the ‘presence’ or ‘proximity’ experienced during a telephone conversation? Where is that ‘togetherness’? Architects know that designing a public phone booth is the hardest commission an architect can get, and they are very pleased that mobile phones are doing away with the need for public booths, precisely because what ‘happens’ during the telephone conversation does not connect to ‘where’ the bodies are. In the movie you can sometimes see both partners in the conversation, each on one half of the screen. But where is a split image? I do not want to give more examples here, but merely point out in what follows that the transformations in the concept of ‘place’ are not only making difficulties for architecture and urban planning, but may also affect political and legal concepts. What would follow from the fact that it is no longer possible to define the distinction between ‘private’ and ‘public’, the relationship of the ‘public’ to the ‘political’, or the concepts of freedom and unfreedom, in terms of space and accessibility? It is no longer self-evident to equate the private and the public with ‘home’ and ‘street’ or ‘square’, respectively, nor to identify street and square with the ‘political’ space. It is no longer self-evident to consider the private as a domain, that is closed off from the world and borders on the public. The ‘basic experiences’ that, for such a long time, ‘intuitively’ and prototypically stood for what freedom and political participation come down to, are losing power and validity. They seem to be no longer ‘valid’, without having been replaced by others.

I will clarify this by presenting two analyses, which do certainly not cover the entire scope of the issue, nor even cover sufficient ground for drawing any conclusions. My sole aim at this point is to illustrate my point and present the problem.

In the first analysis, I will look at the status and the meaning of the house or residence, and (closely related to that), at the presumption and expectation that the citizen has a fixed ‘place’ in society. The ‘fixed place’ should be taken literally here: today, a civil identity is connected to an abode or ‘domicile’. The domicile is the place where a person can be ‘reached’ and ‘addressed’. People are supposed to live somewhere. Living implies a durable connection with a place – a house or a flat – as well as an identification with it. Home is the place where one can talk to someone, where one goes to wait for someone and meet someone. It is the place that cohabiting people share with each other. The fixed place that grounds a life is considered as an essentially private space. The place where a person can be reached is also the place where that person withdraws from the public realm. But because the ‘exterior’ of the private space always borders on the public space – and because, in aristocratic and middle-class residential cultures, a part of the interior is explicitly conceived of as a public ‘reception space’ – the house (the façade and sometimes a part of the interior) does ‘uphold’ the public appearance. The house traditionally represents the person: it is perceived and read as a bearer of his or her social identity and – in the era of individualism – even as the expression of a personality. In other words, the house is a private space with a public face. The house is always also on display; it is façade.

However, the massive introduction of transport networks and the fact that human relations and communications are now largely technically mediated through communication networks are reducing the impact and diminishing the import of this identification. They are reducing the representativeness of the home. First, because the transport networks increase people’s radius of action, making their social contacts more dispersed and one-sided. It is quite common these days not to know where or how one’s closest colleagues or associates live. The ‘public meaning’ or representativeness of the home is eroded even more by the new information and communication channels. Modern communication technology disconnects the home from the communication space where people meet ‘virtually’. In the virtual communication space, the house where real fingers ‘really’ type on the keyboard does not appear: the web page is the new ‘façade’. Inevitably, this erodes the representativeness of the home. When one can find a personal website via a single Google search or find on the Web enough information to put together a file on a person, what meaning could a stone façade still have, or the furnishing of a living room?

This development is reinforced by the second generation of communication media. For the post and the ‘classic’ landline telephone, the domicile remains crucial: the telephone is plugged in at home. In first-generation communication networks (post, landline telephone), the contact is virtual or ‘delayed’, but the home continues to ‘mediate’ and ground a person’s life in a particular place. The home is ‘headquarters’ and therefore remains a meeting place. The ‘address’ is not yet a position in the network itself – like an e-mail address –. It is still a place in the world. The most recent means of communication, however (internet, mobile telephone) have divorced accessibility from ‘domicile’. Accessibility, speaking, and the meaning of what is said are no longer connected to the location of the speaker. Addresses are mobile, people carry their address on them, and they can be reached anywhere. They are their own headquarters. This has major implications for the way the space is used. Before the introduction of the mobile phone and wireless internet, appointments needed to be made well in advance, as a person who was already on his way could no longer be reached. These days, people use their mobile phones to agree ad hoc on where and when they will meet, based on the ‘positions’ of the persons involved at that moment. It makes no difference from which real place one plugs into the virtual space that guarantees the continual reachability of everyone and the ubiquity of all information. Even togetherness in private relationships is mediated by the new technology: when a mother and child both have a mobile phone, the mother is always ‘present’ and she knows at any moment where her child is without a house mediating this proximity. When ‘addresses’ thus become mobile and reachability is disconnected from domicile, the home loses its social importance and its representativeness. The private no longer borders on the new ‘virtual public space’ where everyone is virtually together, and (for the time being) one cannot see the ‘private spaces’ from the virtual ‘public square’. The houses therefore lose their ‘façade’ or face.

What do ‘privacy’ and freedom mean, what is ‘public space’, and how political is a public space, in the light of these developments? Architects and urban planners are not the only ones who realise that the traditional way in which the social structure and social relationships are translated into terms of space is no longer suitable. Even the basic images that supply the metaphorical basis of many political and legal principles or distinctions have lost their ‘validity’. How ‘isolated’ is a person who carries a mobile in his pocket? How public is a telephone conversation held by a passenger on a train? What does it mean to be free to move in a ‘public’ space that is not at all ‘anonymous’ anymore? (The average Londoner is filmed by security cameras 300 times a day.) How ‘political’ is a ‘public square’ when virtual spaces have opened up besides this ‘real’ space, which ‘virtually’ bring together millions of people? In any case, the concept of space in which public and private spaces delimit and exclude one another is no longer adequate, and the home has lost a lot of its social importance. The home seems to be increasingly acquiring or set to acquire a temporary, intimate and secondary quality, practically without a public exterior.

The second development that deserves attention because it is the accepted spatial expression of political and legal concepts – and therefore, in my view, affects the intuitive understanding of those concepts – is complementary to the loss of representativeness of the home. It is a double development, connected to the two possibilities offered by the public space: freedom of association and freedom of assembly. The two developments are, first, the loss of anonymity in public spaces, and secondly, the loss of political relevance and of representativeness of those urban spaces – of streets and squares.

First, the loss of anonymity. Freedom implies freedom of movement. However, just being free to move without anyone interfering, while continuously being followed or watched, is intuitively no longer perceived as ‘freedom’. And yet that is the effect of the new information networks. People who move freely leave traces wherever they go. The development of the new information and archiving techniques have turned the world into one large virtual carpet of snow in which every action leaves tracks that can be combined and used in ways that are uncontrollable and unpredictable. How ‘private’ is life indoors when housekeeping purchases, telephone calls, library use, electronically purchased train tickets and internet surfing behaviour are all saved and stored someplace (automatically and as a matter of course, even without anyone being curious)? It has become difficult to think of ‘privacy’ in ‘spatial’ terms, i.e., in terms of ‘private space’ and ‘seclusion’.

Next: the representativeness of the urban space. Before the new communication technologies were introduced, meeting someone or attending a political meeting involved going ‘outside’, leaving the private space and going out into the ‘public space’. The public space even mediates in private relations: to meet or visit someone, you have to venture out of doors. In a democratic society, the public space, and in particular the city, made up of ‘streets and squares’, was – and still is – identified with the ‘political space’: essentially, it is considered as a space for meeting and discussion, for protest and consensus, argumentation and decision-making. The architecture and urban planning that give material shape to the public space has defended the public space and the city in this sense, especially since the seventies, against the functionalisation and objectification of that space as a result of the large-scale construction of the transport networks, and against the ‘voiding’ of that space by the creation of that second, virtual, technically mediated communication space. The starting point of this tendency in architecture was phrased in succinct and simple terms by Louis Kahn in a lecture he gave to architecture students in 1972, in which he summarised an argument that he has already presented at the last CIAM Congress in Otterlo in 1958: ‘The city is only a part of the inspiration to meet.’ [1] From this, it follows how architects and urban planners should think about architecture and the city: ‘but if you think of the street as a meeting place, if you think of the street as being really a community inn that just doesn’t have a roof... And the walls of this meeting place called the community room, the street, are just the fronts of the houses...’ [2] ‘And if you think of a meeting hall, it is just a street with a roof on it.’ [3] It is abundantly clear that Kahn was defending something that was disappearing.

My point is certainly not to downplay the social importance of the street. On the contrary. Social life still consists to a great extent of pre-modern relations that are based on literal, physical proximity: being neighbours, sharing the same physical space. And these very real and physical relations are very important, in particular for those age and social groups that are less mobile than others. But it would be totally wrong to still consider the street as the primary political space, as the ‘agora’ and therefore as the ‘speaking place’, just because it (still) remains an important social and existential space. What needs to be reformulated here is the relationship between ‘speaking’ or ‘having a voice’, between ‘speaking in public’ and space. It is this connection between the public space, the ‘agora function’ and discourse that has become much less clear-cut.

The key argument here is that the public space – the space of streets and squares – can not be considered as a speaking place anymore, but has become a place of spectacle and spectatorship, and has therefore lots its political relevance. The public space, is now the space where one is free to move, to look and to choose: it is the space of consumption. The dominant social logic that now regulates people’s relationships with what lies outside the private realm and that determines the social rules in the ‘public realm’ is not the logic of discussion, consensus and disagreement, but the logic of consumption. The underlying primitive ‘experience of freedom’ does not seem to be that to speek freely or of being free to go wherever one wants, but rather that of being free to buy whatever one wants. However, this freedom of consumption has a very deceptive political relevance.

The logic of consumption is fundamentally different from the logic of need and necessity. The traditional (urban) market is a public space where interests meet and fight one another, and where the parties will maker peace, will have to arrive at an agreement – a ‘price’ – through negotiation. This makes the market into an important social space, where business relations are made and maintained and where shared interests and agreements are woven into a conflictive but very real social tissue. But cities have changed, the urban condition has changed. However, consumption does not happen on the marketplace, but in solitude in front of the show window. Consumption does not start from needs and is not geared to negotiation and agreement. Its driving force is desire. It demands a daydream atmosphere in which a person is left alone in the company of a quantity of things, forgetting about money and reality for as long as possible, or until he or she unexpectedly and accidentally comes across the object that is ‘missing’, which then transforms, in a surprising-mysterious way, into an ‘object of desire’. In the second movement, the shopping street or the city itself is turned into one large shop window, in which the consumers, who have fitted themselves out with an ‘image’ through their buying behaviour, are exposed to the critical gaze of all the others, and start judging those others themselves, as it they were objects in a shop window. However, these forms of ‘encounter’, the purchase of a thing, or the attention paid to a person’s looks (or the refusal to look at any thing or to buy anything), are never the result of negotiation or discourse. They cannot be measured against a need or a necessity. Consequently, the consumer can never be asked to give reasons. What decides is the irrational ‘I want’ or ‘I don’t want’ (to which ‘I want to be able to want’ = ‘I want money’ is the underlying desire). Consumer logic is arbitray, utterly based on personal desire and personal taste, and sees no problem with that. It offers the experience of a freedom that is not answerable to anything or anyone. But this roaming and freely desiring subject is not a political subject. A consumer’s choice, precisely because it is divorced from any conviction or argumentation, has no political import and therefore cannot be considered as the expression of an opinion. For the consumer does not distinguish the way one elects politicians from the way one chooses a car. The dominant myth of the street is de facto the ideology of populism.

In the light of the objectification of the public space by technology on the one hand and the individualisation of the public space as part of commercial logic on the other, I believe that the situation calls for a reconsideration of the place and meaning of the so-called semi-public spaces. After ‘the fall of public man’, these spaces still function more or less as speaking places. These semi-public spaces remain essentially theatrical, thanks to their threshold. That implies that these spaces are only conditionally accessible – they can be entered on condition that one plays along. Because the theatre, like the school, the city hall, the library or the museum, is a separated public space. This separation automatically implies violence and exclusion: the separated space is dominated by power; certain groups have easy access while others are barred. But the threshold is more than an obstacle. It also marks a transition from the street to a conditioned space: one may enter the theatre or the museum on condition that one ‘plays the game’ and takes part in hat goes on inside it. The university, the city hall, the library, the museum – as well as a session of parliament, or a court – are theatres. The theatre is an exceptional situation in which not only the actors but the spectators too are cast in a role, and must leave behind at least a part of themselves on entering the playing field. Just like the actor is not himself when he plays a role, the people who play the audience in the theatre are no longer ‘themselves’. They are participants in a discussion that goes on within the space of an institution. The street certainly offers a spectacle, which can be fascinating from time to time, but it is no theatre: consumers do not play a role, but are simply ‘themselves’.

Modern civil societies have divided social life into different spheres which each have their official logic and specific activities. The decisions that are taken in each sphere are checked against the specificity of the sphere. For instance, religion and the acquisition of knowledge are different from business and from national defence, law from morality, art from science and from sports, and the private sphere of life differs from public life. The autonomy of these spheres is relative and must always be negotiated with adjoining or overlapping spheres. Although this autonomy is therefore a fiction to a certain extent, it does open up, for each sphere, a playing field that is governed by a specific logic. This logic determines the grounds to which one can refer and excludes other arguments, which are valid in other spheres or fields. The game logic is always imposed and works as if, because in each field, there are de facto always different forces and motivations at work. The invoked reasons and goals are always cover-ups and pretexts: all the social and psychological mechanisms and all the motives and impulses that determine human behaviour everywhere are fully in force in every field. However, the point is, that, within a game, one cannot invoke the reasons that are actually at play. One must be capable of at least hiding them and, on top of that, one must come up with plausible arguments that are valid in that particular game. One must at least plausibly pretend that law is really about doing justice; that science is dedicated to the disinterested search for the truth and for insight; or that art is not about money, but is practised for its own sake. Whoever wants to play is obliged to play a part, to leave his or her ‘self’ behind in the dressing room and to play or stage the actor that is postulated by the game itself. The semi-public spaces are public spaces: anyone can enter them, but only on condition that they are willing to speak ‘the language of the institution’, i.e. at least to pretend that the game is true. And all those who play the game also substantiate the whole enterprise. Their ‘pretending’ is what turns the game into a real event: the decisions taken within a specific field must be ‘plausible’ and are thereby effectively tested against principles that are valid within that field. Rationality needs theatre to live.

It is a debatable question whether – or perhaps: how – traditional spaces, or the civil city-of-streets-and-squares, has ever been a ‘conditional public space’. But it is certain that, in specific circumstances, the so-called ‘public space’ has really been a political space, i.e., a space where the individual took up a role and ‘took part’ in a joint event or a ‘general interest’, by participating in the discussion on decisions, or by affirming the shared values and principles in his or her behaviour. Little seems to have remained of that in the way the public space is shaped and experienced in the contemporary city and landscape. Rather, the street has become a myth: a powerful reference in a mediatised populist discourse, that imitates and evokes the ‘street’ and ‘freedom of speech’ in the media space. The reality of the ‘public consumption space’ and of the unorganised media space is an endless juxtaposition in which everything is uttered without ever eliciting a critical reaction and without checking against tradition. In these circumstances, the political importance of the institutional spaces, which still literally and architecturally divide the private from the public, and who check what is said and done against criticism and tradition – against what has been said and done before – seems to be crucial.

The indifferent or dismissive attitude of architecture towards the specificity of the institutional spaces shows a lack of awareness of the nature and importance of these so-called ‘semi-public’ spaces. Semi-public spaces are mistakenly believed to be less public spaces. For similar reasons, the ‘wholly’ public street is falsely held to be the most important public space, and the place where it is most important for society to be successful. But this view loses sight of the fact that, within those institutions, large parts of the social activity can be ‘conditional’, and that these ‘conditions’ guarantee that certain improper forces and interests can be put ‘out of action’. This implies, for instance – depending on the circumstances and the region where a person lives – that the logic of the ayatollahs or that of the managers can be kept outside the university, precisely because a university is a university and not a mosque or a company. A field that loses its autonomy is colonised – by a political system that cannot tolerate civil liberties or by the consumer logic of the street. In this process, one also loses sight of the fact that the ‘conditional’ nature of an institutional field also applies to the visitor. The visitor is assigned a role, a responsibility, and a dignity. The awareness of this role implies that encounters within the institutional space are not spontaneous, informal, or ‘ordinary’, but are mediated by the ‘object’ that is embodied by the institution. This means that the superb freedom and irresponsibility with which a customer chooses a new car, a travel destination or a television programme do not come into play when that same person enters a museum or wants to study, precisely because a museum has to show what the museum believes is important, and because a school must introduce its students to knowledge, and acquiring knowledge is not like buying commodities. An institution doesn’t have clients. For the time being, in the civil society, a large part of the social decisions are still taken within these autonomous, institutionalised fields.

To sum up, I believe it is important, not only for architects and urbanists, to clearly formulate and realise, that crucial and formative conceptual structures, such as the distinction between the private and the public, and highly important presumptions, such as the idea that a public space is almost by definition also a political space and vice versa, are gradually becoming ‘false’ because the relationship between speaking, speaking in public, and space is fundamentally changing.

Secondly (but now I am talking politically) that it remains very important, in this respect, to affirm and use those spaces that still fit into the traditional ‘spatialisation’, and to protect and reaffirm those institutions and places of ‘public discourse’, such as a university auditorium, or a museum. An institution, as far as I can see, needs an actual, real space, and bodies who want to play the game. Internet, I think, will not produce institutions. For the time being, these semi-publis, institutional spaces are irreplacable to be able to discuss and critisize, and think about what is happening ‘outside’, in the streets and in the new, virtual ‘agora’ of the media.

Note: Bart Verschaffel's paper “Public Truth and Public Space”, was given at the conference, ‘Truth and Public Space’ organized by the Catholic University Leuven in Brussels, Sept. 21 – 23, 2005

« Causes for Concern -Michael D. Higgins | There is an enormous sadness at the heart of Europe by Michael D. Higgins (1999) »